All the News that's Fit to Post, Part 4: Trump on Trial, and Why ITN Will Never Change

The serene presentation of Wikipedia's front-page "In the news" section belies the messy truth behind the headlines: a never-ending newsroom argument about matters both serious and silly

In the previous three installments of this series about how Wikipedia editors choose headlines to feature on the site’s main page, we have peeked into the history and back story—“Part 1: What is ‘In the News?’”—and examined the cultural differences that favor some sports news over others—“Part 2: The Super Bowl and The Boat Race”—and even how death and tragedy is weighed—“Part 3: Another Day, Another Shooting and Other Debates About Death”. Today we’ll examine ITN’s trouble covering Donald Trump, and evaluate some reasons why ITN is the way it is.

Why ITN is reluctant to cover Trump’s trials

With some hesitation, our survey concludes with a look into how Wikipedia’s “In the news” (ITN) feature has handled the many legal challenges facing the former U.S. president and presumptive 2024 Republican nominee. Trump’s career has been forged in the courtroom as much as the boardroom or the voting precinct, and in fact Wikipedia has two separate articles on the subject: one about his “personal and business” legal affairs, and another “as president”.

None have been so newsworthy, and so vexing to ITN, as the four indictments which were handed down in the spring and summer of 2023. One might think indictments of a recent world leader on undeniably serious charges would be an easy call. But nothing is ever easy at ITN. To understand why ITN has been resistant to spotlighting Donald Trump’s legal jeopardy, we must understand two separate rules: one that fails to meet the moment, the other simply misapplied.

First let’s revisit the essay “How ITN works (and how it doesn’t)” and its section on which news stories are “disfavored”. One is “penultimate items in a sequence of events”, i.e. when a news story is only one stop along the way to a more final headline, it’s better to cover just the last item to avoid repetition. Indictments are certainly not the last event in a trial—not to mention Trump is constantly in and out of court—so editors quickly become tired of repetitive news items, and want to stop covering them. Which is, alas, a neat little microcosm of the conundrum journalists wrestle with covering Donald Trump in the first place.

The second is a section of the “Biography of living persons” policy—which requires giving the “greatest care and attention” to articles when individual reputations are on the line—known as “BLPCRIME”. One of its stipulations is that criminal charges against non-public figures are sometimes omitted, as Wikipedia observes the presumption of innocence found in the laws of many countries. For non-public figures, this approach makes sense. But sometimes it is applied to public figures, as if it was just a good rule of thumb.

Both arguments lead many ITN participants to a position of caution, sometimes expressed as: “we post convictions, not indictments”. So, how did Trump’s four indictments fare at ITN? Let’s find out:

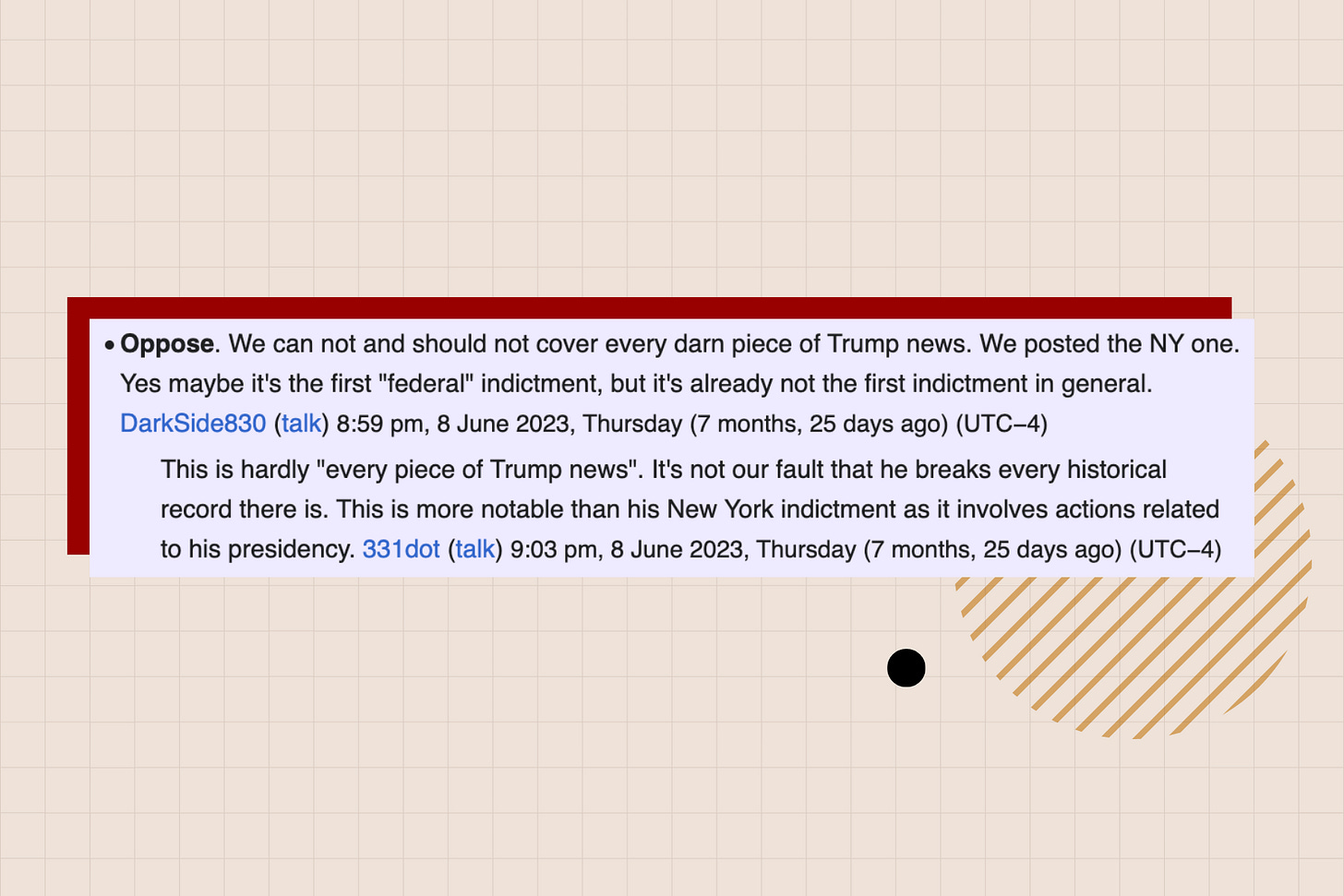

Indictment one

The first of these debates occurred last March, when Trump was indicted in New York for falsifying business records—the Stormy Daniels case. BLPCRIME came up eight times. More, if you count typos: “How many times do we have to talk about WP:BPLCRIME in this space? Exhausting.” “It isn’t a violation of WP:BLPCRIME to say that an indictment of a former US president is newsworthy.” There were some good old U.S.-centrism complaints as well: “This is a worldwide news page, not a list of news about U.S. politics. I’m so tired of this american/western bias here”. And of course: “Oppose since when did we start posting indictments instead of convictions?” In reply, another editor wrote: “I mean, I know it’s not conventional, but this indictment strikes me as being uniquely consequential and newsworthy.” Nevertheless, 7,200 words later, a “slight majority for posting” was not considered consensus enough. No blurb.

Indictment two

In June came the more serious indictment in Florida for mishandling and refusing to return government documents to the National Archives. Opinions looked much the same: “Support. Historically significant; no former U.S. president has ever been criminally indicted on federal charges.” “Oppose For now. Post conviction.” “Support Unprecedented and the top story everywhere.” 9,100 words of debate later, the blurb was posted—without formal review. If an editor had performed a review and shared their findings publicly, they almost certainly would not have posted the blurb. But this time, supporters took the initiative, and opposers did not press the issue. Demands to pull it were issued, but ignored, and so it remained.

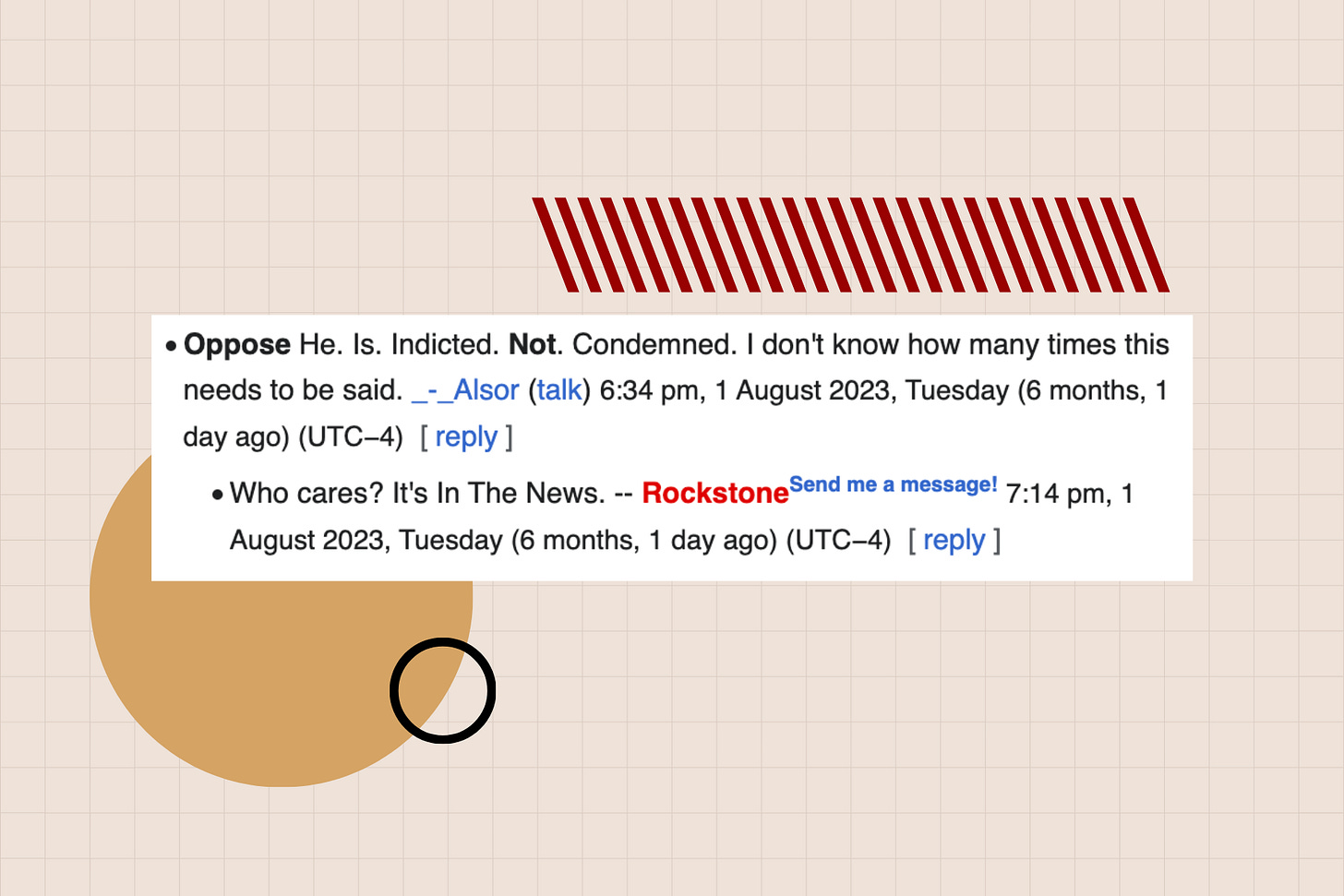

Indictment three

In August Trump was indicted in DC for attempting to overturn the 2020 presidential election, arguably the most significant case because it focuses on Trump’s actions on January 6, 2021. This time only 5,500 words of debate were needed to decide against posting it. Many sharp words were exchanged, but the result can be mostly summarized with this early comment: “Weak oppose While I can be convinced, this isn’t the first time he’s been indicted, and it feels somewhat unnecessary to post again.” Result: not posted.

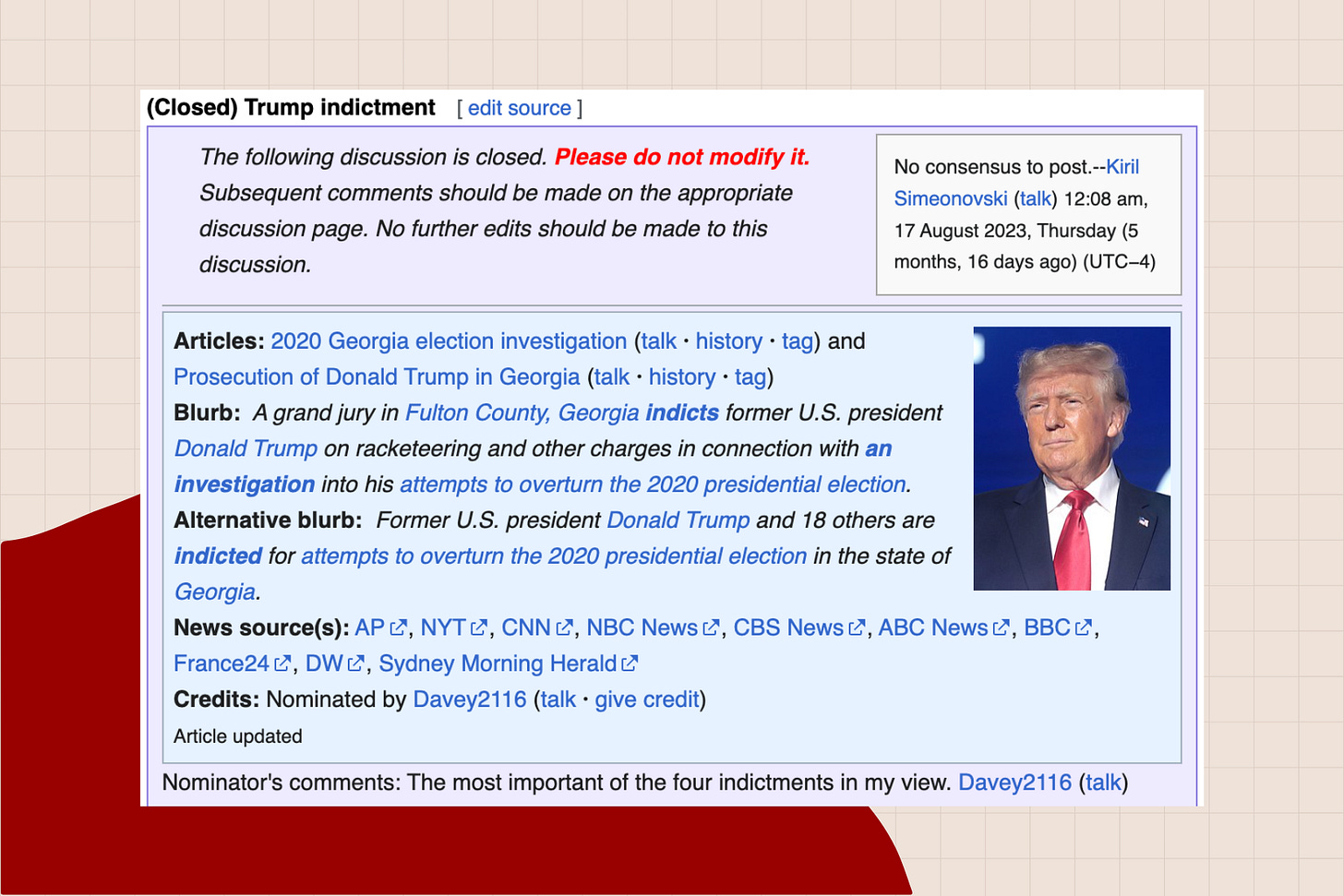

Indictment four

Later that month Trump was indicted in Georgia on charges similar to the DC case. The nominating editor argued: “The most important of the four indictments in my view.” Others did not share this view: “Fortunately, this should be the last time that a Trump indictment is nominated. In fairness, the indictment is sprawling, but the legal issues of Trump have already been covered on ITN.” But does one blurb mean it had been covered sufficiently? Having read through so many ITN debates, I think it’s actually rather common for editors to confuse their own deliberation of whether to post something with it actually being posted. All the best intentions, just a misremembering borne of being too immersed in too many similar debates. The fourth indictment also fell short of consensus, and was not posted.

Verdict

May it please the court of opinion, The Wikipedian finds, of four major criminal indictments of the former (and very much possibly the future) U.S. president, only one was deemed worthy of posting to ITN—and that one almost didn’t happen.

A postscript: later in August, Trump turned himself in to Georgia authorities and submitted to a mugshot—an event that by itself was national news. And so it was nominated at ITN, albeit apologetically: “I know many will oppose us becoming ‘Trumppedia’ but I think it’s worth taking a look at this story.” Three “opposes” and no “supports” later, the nomination was closed. The reviewing editor’s final comments: “I think we all know where this is going.”

Never change, ITN

Why must ITN be like this? The Wikipedian sees a few reasons why it is, and also why it is unlikely to change.

The first has to do with its structure. ITN struggles to define its ethos because it is so much unlike the rest of Wikipedia. Where editors working on regular Wikipedia articles have no maximum word count, ITN operates within very tight formatting restrictions. Where Wikipedia articles take the long view, covering a topic from its origins through the present, ITN must take a narrow view of some very weighty topics. Where Wikipedia has no deadline, ITN is nothing but deadlines: a few days to post a name to RD, a few hours to weigh in on the latest news—or maybe just a few minutes. Answer now, or the wrong thing might have forever happened.

In this view, ITN functions much less like a Wikipedia article and more like a subreddit—a highly dysfunctional one.

Second, a more cynical view: ITN is not an editorial operation. It’s a fight club. ITN may have started out as a place to post articles, but it has become a place to blow off steam from one’s regular editing. Unlike RfC discussions or Arbcom cases, there are no long-term stakes. Stressed out from arguing over something that matters? Why not drop in on ITN and throw a spanner in someone’s works. Even better if you have the opportunity to annoy someone who has a different set of interests, national pride, or political viewpoint than one’s own.

In this view, one might argue ITN does not struggle at all, in fact it’s very successful at providing opportunities to get in an argument.

Finally, consider it through the lens of whether ITN serves its readers well. As of this writing, the main page of Wikipedia receives nearly 5 million views each and every day. When those readers glance at the ITN box, they see news items that may have just occurred, or perhaps several days ago. They may learn about events they would never have heard about, or their eyes may glaze over. They may feel a spark of recognition at a news story they care about being so prominently featured, but probably not. Maybe the “fault” actually lies with the readers. There are too many of them from too many places with too many different points of reference for five or six bullet points to capture the news of the world in a way that is meaningful to everyone.

In this view, ITN didn’t break, instead the mission was always impossible. This one is probably the most cynical of all.

If anything is going to change—and it probably won’t, but let’s imagine—it might start with something called the “DICE standard”, as conceived by the editor behind the “How ITN works (and how it doesn’t)” essay. DICE stands for depth, impact, consequences, and encyclopedic suitability. Quoting from the essay, which still remains a public draft in the user’s account, editors should consider:

The length and depth of coverage itself

The number of unique articles about the topic

The frequency of updates about the topic

The types of news sources reporting the story

This seems like a reasonable place to start. Which some might say is exactly why ITN will never adopt it. Another possibility is that ITN could assimilate all this data and nothing could change: editors would still want to put their thumb on the scale, because the point is not making sound editorial judgments—the point is about exercising one’s power to restrict others from getting what they want.

There was a popular saying in software communities of an earlier generation: “given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow”. Typically this means a critical mass of aligned developers will sort out all the problems in a piece of code. ITN shows what happens when the crowd, in all of its wisdom, is not aligned. ITN doesn’t lack for eyes, but it does lack for vision.